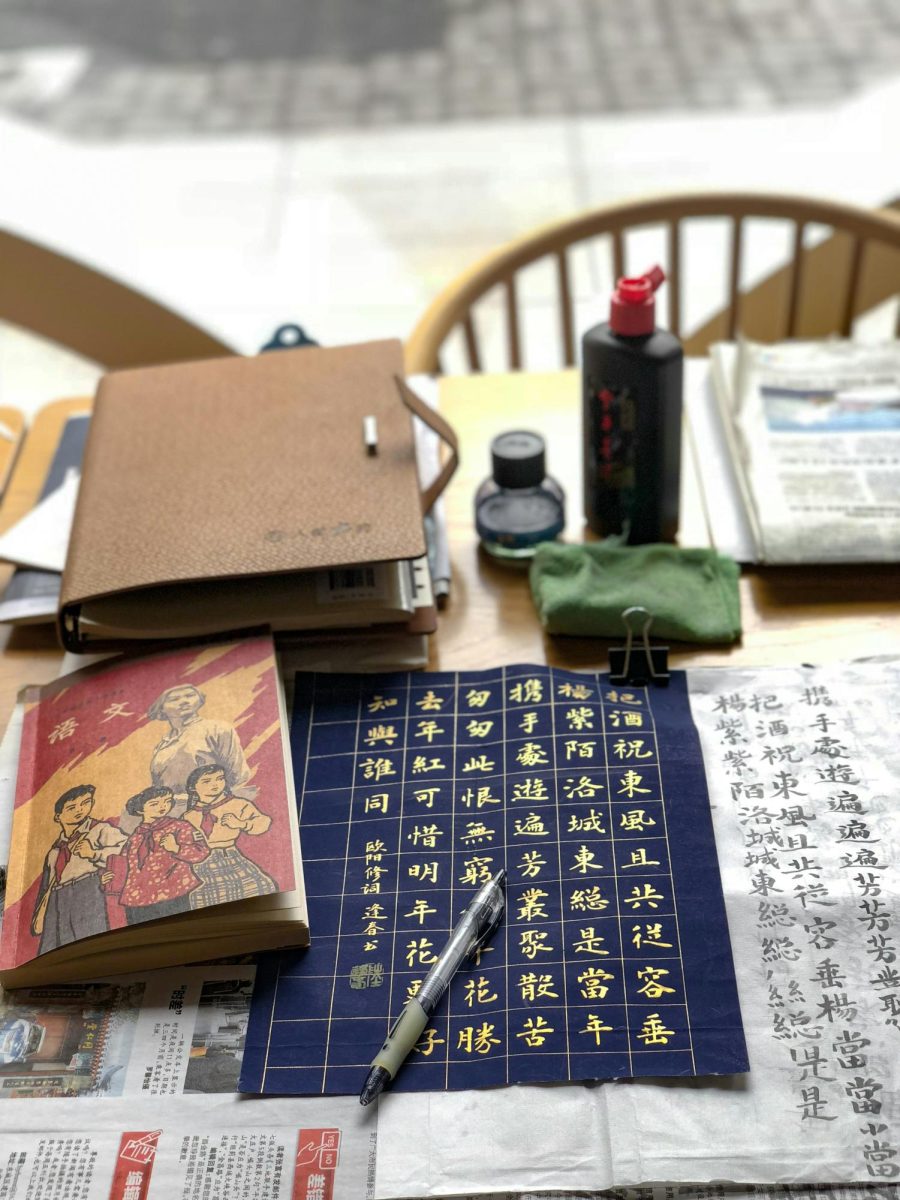

Language. It’s our means of communicating thoughts and ideas from one person to another, whether consciously or subconsciously. It takes the form of spoken words but also of the slightest movement of a hand. It is written on paper for keeping and sending, placed on billboards and signs or etched into trees and sticks. In every aspect of our lives, no matter our background or profession, language remains fundamental to the human experience.

I speak English, but I have some understanding in Tagalog and Bisaya because those are my family’s home languages. I have also learned conversational Turkish after living in Istanbul for a semester and can write in an elementary level of Japanese. Within my own life experience, learning and knowing other languages has helped me understand my own community and the world around me better, whether that be through my schoolwork or through meeting different people every day.

Now then, why is it that there has been a sudden drop in foreign language enrollment in higher education, including CU Denver? The Modern Languages Association, also known as MLA, noted a 16.6% drop in enrollment for languages other than English between the years 2016 and 2021. You would expect that, with our quickly diversifying world, more people would be interested in picking up a new language, but that has not been the case in recent years. While commonly taught languages such as Spanish and French remain on their pedestals with the most enrollment nationwide, and other less commonly taught languages such as Japanese and Korean have seen a rise, generally, we have witnessed the same phenomena – college students simply aren’t taken as many language courses anymore.

When asking students about whether or not they were taking or have taken a language course outside of English at CU Denver, 86% of students answered they have not taken a language course. When asked about their reasoning, 26% of those who answered “no” having had already achieved their language requirements in high school. Another 15% said their major didn’t require language credits or that they simply didn’t want to take foreign language classes. Among other reasons were time constraints, the use of language apps like Duolingo, and bilingualism. Only a few students showed interest in taking foreign language classes later in their college careers.

This begs the question of why. Why is it important that students continue learning new languages within their higher education careers even if they are already bilingual or have reached their language requirements in high school? Alyssa Martoccio, the current chair of Modern Languages at CU Denver, has her own take on it. The Capabilities of Language Learners

Martoccio has had the desire to learn new languages since she was 12 years old. She currently teaches a handful of courses, including Spanish and linguistics. Regarding continuing foreign language courses in higher education, Martoccio shared, “There’s some data that says that students who can speak another language are likely to have a higher earning potential, get[ting] paid 5 to 20 percent more than monolingual students … and are more desirable on the job market.”

Language learning goes beyond that of polylingualism, benefiting students in aspects of general memory and critical thinking skills. In Martoccio’s own words, language learning “helps you think differently and be more open to new possibilities.” A Cambridge study in 2022 found that language learning functioned as an effective workout for the brain, and those who were naturally bilingual or committed to a foreign language experienced enhancing communicative and creative skills. Being exposed not only to written and spoken language but also to the culture that comes with participating in a foreign language increased students’ ability to think critically outside of an American mindset.

Many students using Duolingo and Drops are able to learn practical words and phrases, and those applications certainly assist in the acquisition of vocabulary, but the cultural and social aspects of language that you would receive within the classroom setting and in the practical use of that language with other peers is lost. Martoccio stated, “I have nothing against AI, but using AI doesn’t help [us] understand the cultural things.” Martoccio continued to share that there are different cultural implications to certain phrases and actions in a language that have deeper meanings than one may think. The result of students ending their academic language career early on is the loss of understanding towards cultural nuances in favor of more ethnocentric mindsets.

A good example of a less commonly taught language that has suffered from both misunderstanding and declining registration is Arabic.

A Case Study on Language Learning: Arabic

Nowadays, Arabic is crucial in understanding the Middle East, which has taken much of the media by storm as of late. However, Arabic language courses have had an enrollment rate of only 34.3% nationwide since 2021 according to MLA, representing a decline in student activity as well as instability in semesterly enrollments. This represents the ironic trend of the critical need of Arab speakers in the Western world in relation to the lack of those willing to learn the language.

I interviewed Elizabeth Huntley, who teaches both Arabic and Linguistics at CU Denver. Having studied in Syria and worked in Egypt for studies abroad, Huntley appreciates Arabic not only as another foreign language, but as a language that is rich with culture and displays an extreme importance to our current understanding of global society.

“I was curious about [Arabic], and [I] remember 9/11. I think it definitely raised people’s awareness of ‘oh my goodness, we don’t live in a bubble,’ and that it’s important to understand that part of the world.” Huntley then explained the importance of teaching language as a global language, including its implications on world history and current affairs. “My French teacher did a really good job teaching French as a global language, so we learned a lot about colonialism and immigration to France from the Middle East and Africa.” In her Arabic class, Huntley not only teaches Arabic as a language but also demonstrates the cultural significance of its dialects, such as Modern Standard Arabic in relation to Egyptian Arabic, and phrases that are embedded into general Arab culture.

Christine Sargent, an assistant professor of Anthropology at CU Denver who has also studied in Jordan, adds on to Huntley’s stance, saying, “The world is much bigger than it is presented to us as, and our role in it might not be as straightforward or positive as a mainstream narrative presents us with … To understand a people’s view, you should probably be able to speak their language somewhat adequately. I think it’s an ethical and political commitment to learn a language but also a cultural and social one.”

To comprehend the issues of the Arab world regarding politics, business, etc., knowledge of the language culturally is needed to fully grasp what someone speaking in Arabic is trying to say. Huntley shared, “Arabic [is] so full of expressions and jokes that you use with one another that don’t come across when you’re using [an AI] translation-based approach … You will get a very flat understanding of another part of the world.”

Concluding Remarks

Arabic is only one of many languages that are lost to the general requirements of math and science. Even German continues to struggle with enrollment across the U.S. I think that we as students often forget that foreign language is not an independent study – it, too, is a liberal art. Christine shared, “Even though English is a global and hegemonic language, if you speak another language you’re communicating the value of other languages.” As a multi-lingual society, we in the U.S. often forget that it is usually the responsibility of “others” to learn English, when that international relationship could be reciprocal.

Christine commented that people are often unaware that bilingual education is a standard in almost every part of the non-English-speaking world. To dismiss language learning entirely would be to narrow your worldview. I am not equating to the need to be advanced in a foreign language; sometimes just knowing how to properly say hi in another language is enough to open the hearts of others.

Learning a new language in higher education proves not only to be a culturally enriching experience, but a socially enriching one too.

“So much of what you start off with is ‘My name is,’ and ‘Here’s my schedule, my family, my hobbies,’ so it’s a natural way to learn about the people around you,” Huntley said. “It is also absolutely a way to open the gate to another world and another culture.”

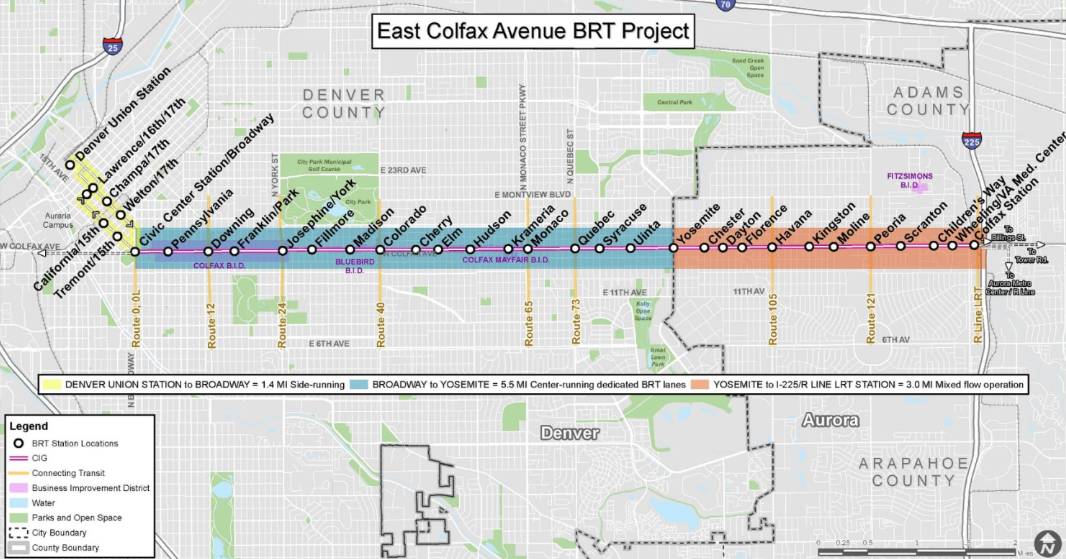

At CU Denver, there are many opportunities to learn a new language. The Department of Modern Languages offers courses in French, German, Latin (as well as medical Latin), Arabic, Spanish, and Chinese. “There are so many different languages [we’d want to open] … We did a meet-and-greet with students and so many wanted Korean, Japanese; I personally would love to have Italian,” Martoccio shared. “Any language that’s a world language would be really helpful.”

However, for a language class to open, students need to show interest and enroll, and that poses the question we face today. CU Denver, are we going to open that gate?